What Else Don't We Know? The Bystander Effect in Hierarchies & Systems

We often fear what will happen when we misspeak. We stay quiet out of fear of being wrong or not believed. But, sometimes, the consequences are too great.

The Dangerous Implications of the Bystander Effect

February 4, 2017. Though it is prohibited, Timothy Piazza is going through a hazing ritual at Penn State. He’s not alone. Eighty percent of all fraternity members experience these “humiliating and sometimes dangerous initiation rituals.” In less than an hour and a half, Timothy downs 18 alcoholic drinks and proceeds to fall head-first down a staircase. As he lies unconscious, the party continues. Fraternity brothers clean up, send text messages, and go about their night — all in front of a security camera — before they finally call campus police. It took Piazza only 90 minutes to drink himself into a stupor, but it took his friends 12 hours to call the police.

This story, however, isn’t some unconventional college anecdote that Piazza will share with his friends. After suffering traumatic brain damage, a lacerated spleen, and an abdomen full of blood, Timothy Piazza died.

College fraternity parties are common and tend to involve alcohol and underage students. This combination often leads to irresponsible behavior, but in 2017 it led to worse: the death of Timothy Piazza.

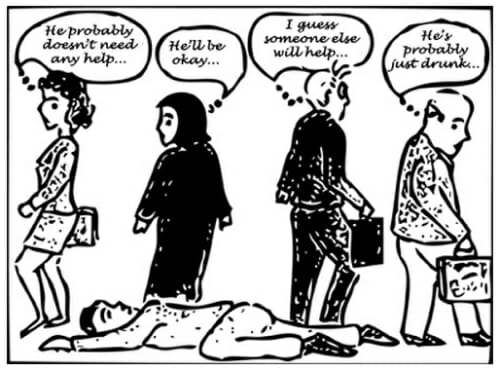

This is the bystander effect which, according to Psychology Today, “occurs when the presence of others discourages an individual from intervening in an emergency situation.”

How Does Spotlight Exemplify the Bystander Effect?

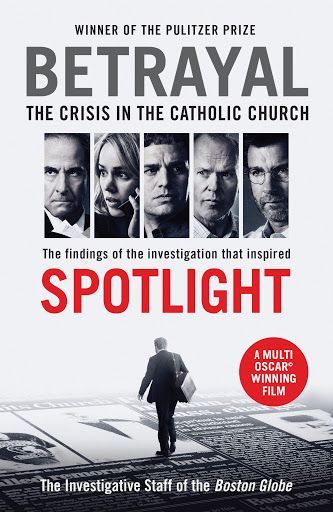

The movie Spotlight (2015) highlights a particular systemic instance of the bystander effect: it allows for an acceptance of exploitation within the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church.

Spotlight is based on the true story of the research team at The Boston Globe that uncovered over 300 cases of child molestation by more than 250 priests. Nobody wanted to confront it; though, within the Catholic Church, there was knowledge of what was going on. The priests were not condemned; they were simply moved to different locations, allowing them to continue close contact with other children.

Spotlight explores the ethics of the bystander effect when Mr. Rezendes, a reporter for The Boston Globe, speaks with a lawyer representing some of the victims. The lawyer says, “Mark my words... If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to abuse one." When a witness fails to call out the abuser, it encourages the abuser to continue because they feel untouchable, believing they can get away with it.

Does keeping silent make you just as guilty as the abuser?

“We need to focus on the institution, not the individual priests. Practice and policy; show me the church manipulated the system so that these guys wouldn’t have to face charges...Show me this was systemic, that it came from the top, down.” – Marty Baron (Editor at The Boston Globe) from Spotlight

The film does not fully address the lawyers who wrote confidentiality agreements for the Catholic Church. Instead, it simply introduces one lawyer, who reached secret settlements with the Church. In reality there were 6 lawyers who worked confidentially with knowledge of the abuse. One person coming out and addressing the entirety of the Catholic Church would probably be shut down. Being one versus thousands creates a difficult situation for people trying to be heard. Even The Boston Globe was initially a bystander. Years earlier, they received leads on the story that they published in 2002, but proceeded to dismiss it.

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church as a whole is also at play. Specifically, local bishops were the most prominent bystanders. With full knowledge of the molestation, they failed to address it properly. Instead, they took what they knew about specific priests and covered it up by simply moving the guilty priests to different parishes. Bishops then gave them various titles, one in particular: “sick leave”. This made it so any record of why they were moved was disguised as innocence. By allowing the guilty priests to continue their work, bishops almost encouraged the wrong behavior.

Child molestation in the Roman Catholic Church, specifically in the Boston area, was directly encouraged by its hierarchy and the way they could use fear to control their congregations. It seems insane that people would "allow" this to happen, but it reveals a larger issue that goes beyond the Roman Catholic Church: What else is being covered up? What don’t we know in other situations with similar power structures?

How Can We Relate?

Even on a smaller scale, it is a proven fact that if you're around others and you see someone struggling, you're less likely to respond, but so is everyone else. We don't speak up because we often believe someone else will. But if everyone shares this belief, no one speaks up in the end. Thus, our silence allows it to continue.

The U.S. Department of Justice states: "Third parties were present at 70% of assaults, 52% of robberies, and 29% of rapes or sexual assaults."

For everyday occurrences, our inaction is harmless, but what happens when things become more serious? How should our reactions differ depending on the situation? Should they differ? If we don't respond to the smaller issues, are we teaching ourselves to not react to the bigger issues?

It is hard to set a threshold for when people should respond to a situation. There is no way to understand every potential situation with so many different variables, but this leads me to another question: As a society, should we be doing a better job standing up for what is right?

No matter the severity, in situations involving the bystander effect, something is not right and nobody attempts to fix it. I think we can all agree that it would be better to have five people turn to help, than none.

How Can the Bystander Effect Impact a Hierarchy?

So, how is the bystander effect exacerbated in hierarchical situations? Humans inherently want to be right. We often fear what will happen when we misspeak. We stay quiet either out of fear of being wrong, or the fear of being right with no one believing us. Both accentuated by the hierarchy and accompanying power disparity. Nobody wants to call out their boss when it could get them fired, and especially not in front of their peers.

A typical business or office environment is another example of a hierarchy. In a study by Harvard Business Review, half of the respondents felt that it was unsafe to challenge beliefs in a business environment, even when the companies had specific mechanisms to encourage people to speak up. Social fears cause a disconnect between what we think is morally correct and what we do with that information.

How Does Racism Play Into an Unjust Hierarchy in America Today?

What does this mean for us right now? Think about systemic racism. In the past few months, the Black Lives Matter movement has become increasingly prominent. Proportionally, many more Black people are killed by police officers than White people. Some may argue this is because African-Americans are more likely to live in lower income neighborhoods, which likely have more crime. But why? Why is there still a racial hierarchy within the United States? What makes it so Black Americans are less likely to live in higher end neighborhoods or succeed in certain fields?

In “The Persistence of Racial Hierarchy and Why It Matters,” author Hank Kalet highlights the power of language in creating or changing reality. He says, “Racism is not just about hate, but about systems that create hierarchies, that enforce the differences.”

The United States has one of these systems.

In the United States, as Kalet points out, there is a history of negative behavior and microaggressions against minorities. This starts with those in power and comes from the top down. Looking back at the history of the United States, in 1973 President Nixon speaks during an Oval Office meeting about what he thinks of Black people’s ability to run Jamaica: "Blacks can’t run it. Nowhere, and they won’t be able to for a hundred years, and maybe not for a thousand. … Do you know, maybe one black country that’s well run?" Let that sink in. The 37th president of the United states, in 1973, just shy of fifty years ago, said he didn’t think Black people would be able to run a country well for maybe a thousand years. Nobody interjected. The negative impact of authoritatively speaking to people without allowing room for conversation or taking time for prior education on the topic is immense. The bystander effect, in this example, manifests itself as a lack of allyship.

It isn’t always intentional. But it's there. The hierarchy of the United States creates a system where people are labeled from the top down, which enforces negative ideas towards minorities in the minds of the American people.

The solution to preventing future injury and death dueto extreme hazing leading, the solution to disrupting systems that encourage corruption, though not simple, begins with one person’s willingness to stand up for what is right. Once we work to prevent the smaller instances of the bystander effect, the larger ones may cease to exist at all.