A Gentleman in Moscow: Embracing Change

We must master our circumstances, growing past the insanity that this year has been and carrying these lessons into life after high school.

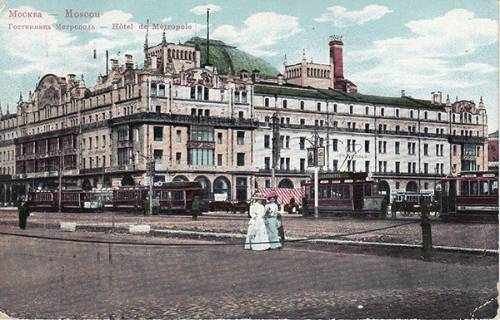

I was supposed to have a normal high school experience. I planned on finishing my senior year with a complete basketball season, with classes without dividers and masks, ending everything with a normal graduation ceremony. That didn’t happen. Instead, the tail end of my high school career has consisted of a “new normal.” “A new normal” where we have sanitizer coming out of our ears, face masks are an accessory piece, and everybody is pessimistic about the world. In the beginning, I couldn’t help but feel pessimistic myself. When I was assigned 462 pages of A Gentleman in Moscow, schoolwork did not lift my spirits. However, I couldn’t help but feel guilty as I read about Alexander Rostov shaping his impossible situation while I complained about mine. At that point, I put the book down and decided that feeling sorry for myself was useless. We all have a story about life smacking us in the face, but complaining about it rather than changing something gets us nowhere. A Gentleman in Moscow encapsulates the power of transformation as Rostov creates a life for himself while serving a life sentence in the Metropol. Towles teaches us that one must grow and change in the face of adversity rather than submitting to it.

Rostov’s most valuable tool is his ability to adapt. As a child, Rostov’s parents fell ill and died. While the Count was only a boy, he knew that he must stay strong for his sister. In those days of loneliness, the young Count was told that “[i]f a man does not master his circumstances then he is bound to be mastered by them” (18).

Flash forward many years, and the Count is alone yet again, the exact phrase echoing in his head. This phrase encapsulates the Count’s attitude towards everything that happens to him while surviving in an ever-changing Russia. This is true for both sides of the coin. When he feels that he has lost touch with the world while in confinement and cannot “master his circumstances,” he contemplates ending his life. Yet he doesn’t.

He finds purpose in the Metropol by working, caring for others, and creating a community to give his life purpose again. After this turning point in his character, the Count refuses to submit and shapes his life to adapt to his new life, thus mastering his circumstances.

Towles’s belief in the importance of change is pretty apparent. “It is the business of the times to change” (75). Today, the times are changing a lot. Every day we get a new wrench thrown into the plans we thought we had. Naturally, the only way to thrive with change is to grow with the times.

As I read A Gentleman in Moscow and reflected on my own life, Towles drew my attention to the silver lining. The irony behind the Count’s imprisonment is that while it initially seemed like a tragedy, it is what eventually saved his life. The government arrested the Count for a poem he wrote, but later on, Rostov discovers that the Bolsheviks would have killed him because of his previous social standing.

“Who would have imagined... when you were sentenced to life in the Metropol all those years ago, that you had just become the luckiest man in all of Russia” (292).

After I read this quote, I thought about the situation some more. At first glance, he became “the luckiest man in Russia” because his imprisonment saved his life. I don’t think that’s what Towles intended with this quote, though. I think Rostov is the luckiest man in Russia because when he was “imprisoned,” it allowed him to find a family in the Metropol. He made the most of a situation that, on the surface, was a life sentence in a room.

Towles illustrates that just because a situation might seem bad on the surface, there is always an opportunity to grow from it.

Flashover to my whacky senior year, and on the surface, it’s awful. But some positives came out of it. During lockdown, I developed new healthy habits like running, and during school, I developed effective methods of working as I was on my own for some time. I changed a little for the better to match the circumstances, kind of like Rostov.

Towles also illustrates the alternative to change, staying comfortable when presented with a new challenge.

In A Gentleman in Moscow, we see an exaggerated version of this with the ever-changing societal norms. Rostov loses his title as “Count” (75), and parts of history are banned (101). Those that adapt to the times, like Rostov, find their place in the world, eventually leading him to become a family man (of sorts). However, those that reject the changing times are consumed by the world around them. In this case, Nina isn't seen or heard of after criticizing the Russian government.

On the surface, this is a historical commentary on the impossible social mobility present in Russia during the 20th century. People that rejected the culture were silenced, killed, or exiled, and those that submitted to it were left alone. But if we look at this from a thematic level, we see Towles using the Bolshevik culture shock as a metaphor for change in our lives. Like Rostov, we can accept it and move on, or we can fight it and end up suffering like Nina.

Change is funny because, in the moment, it's very easy to scoff at. At one point, I dreaded the idea of going to college and being independent, but now I look at it as a chance for me to grow. While college is by no means comparable to imprisonment in an oppressive regime, I still like to look at it like Towles intended. We must master our circumstances; in my case, I need to take full advantage, growing past the insanity that this year has been and carrying these lessons into my life after high school.

This book selection coincidentally was a metaphor for the past year. But how we learn from times like this makes the difference between barely getting by and thriving, just like Count Rostov in the Metropol.